The Swahili Coast of East Africa is a place where time seems to stand still, yet history whispers through every coral stone and carved wooden door. Stretching from southern Somalia to northern Mozambique, this coastal strip has been a melting pot of cultures for over a millennium. The stone towns that dot this shoreline are not just architectural marvels but living testaments to a unique blended civilization that emerged from African, Arab, Persian, Indian, and later European influences.

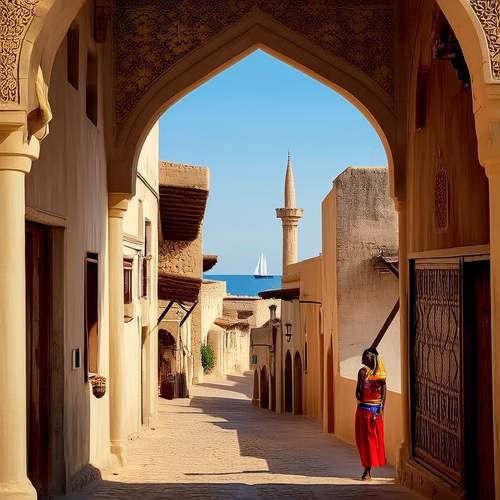

Walking through the narrow alleys of Zanzibar's Stone Town or Lamu's old quarter, one immediately senses the layers of history beneath their feet. The very ground seems to exhale the scent of spices traded across the Indian Ocean, while the buildings display intricate designs that speak of distant lands. These urban centers developed as crucial nodes in the Indian Ocean trade network, where merchants from across the maritime world would meet, negotiate, and often settle down to create families with local women.

The architecture of these stone towns reveals their cosmopolitan origins. Coral rag buildings with ornate Omani-style doors stand beside structures showing clear Gujarati influences. The famous carved doors of Zanzibar, some with brass spikes reminiscent of Indian traditions, others with Arabic inscriptions, perfectly symbolize this cultural fusion. The use of coral stone as primary building material demonstrates how local resources were adapted to create something entirely new - a distinct Swahili architectural style that couldn't be found anywhere else in the world.

Language tells perhaps the most fascinating story of cultural blending. Kiswahili, the lingua franca of East Africa, is essentially a Bantu language with an enormous infusion of Arabic vocabulary, along with Persian, Portuguese, Hindi, and even some English words. This linguistic tapestry developed organically over centuries of trade and interaction, creating a language that could bridge multiple cultures. The very name "Swahili" comes from the Arabic "sawahil," meaning coasts, yet the grammar and structure remain firmly African.

The Swahili people themselves represent one of history's most successful experiments in cultural mixing. While maintaining strong connections to mainland African cultures, they developed a distinct coastal identity that incorporated Islamic practices from Arabia, culinary traditions from Persia and India, and even some European elements during the colonial period. This wasn't simple cultural borrowing but rather the creation of something entirely new - a civilization that belonged to the Indian Ocean world as much as to the African continent.

Religion played a central role in shaping Swahili culture. Islam arrived with Arab traders as early as the 8th century and gradually became the dominant faith along the coast. However, Swahili Islam developed its own distinctive character, blending orthodox practices with local customs and beliefs. The mosques of the stone towns, often modest in size but exquisite in detail, show this unique synthesis - their minarets might resemble those in Oman, but their construction techniques and decorative elements are purely local.

The monsoon winds dictated the rhythm of life along the Swahili Coast for centuries. From December to March, the northeast monsoon would bring Arab and Indian ships to East African ports. The reverse southwest monsoon from April to September would carry them back home. This seasonal pattern allowed for the gradual development of deep cultural connections, as many foreign merchants would spend months at a time in these towns, forming relationships and influencing local culture before returning to their homelands.

Food culture along the Swahili Coast offers delicious evidence of this millennium-long mixing. Spices like cinnamon, cardamom, and cloves from Zanzibar blend with coconut milk from local palms, rice from Persia, and cooking techniques from India to create dishes unlike any found elsewhere. The famous biryani of the coast differs significantly from its Indian namesake, while dishes like urojo (Zanzibar mix) combine African, Indian, and Arab elements in a single bowl.

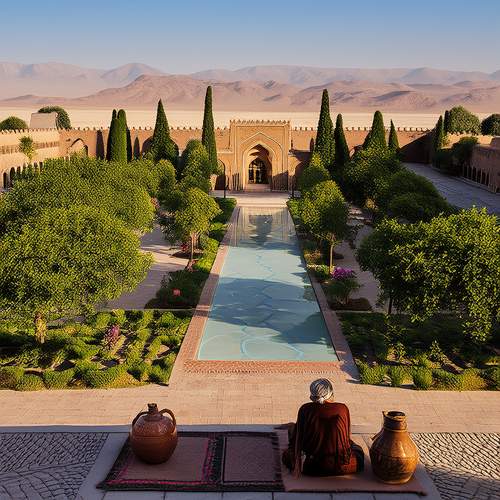

The golden age of the Swahili city-states between the 12th and 15th centuries saw this culture reach its peak. City-states like Kilwa, Mombasa, and Malindi became wealthy centers of trade and learning, minting their own coins and building grand structures. The Great Mosque of Kilwa, with its unique domed roof, and Husuni Kubwa palace complex stand as ruins today but hint at the sophistication of these societies. Chinese admiral Zheng He's visits in the early 15th century demonstrate how these towns were connected to the wider Indian Ocean world.

European arrival in the 16th century disrupted but didn't destroy Swahili culture. Portuguese then Omani domination changed political structures but couldn't erase the deep-rooted cultural synthesis that had developed over centuries. In some ways, these new influences were simply absorbed into the existing mix, adding yet another layer to the coastal civilization. The Omani period, particularly under Sultan Seyyid Said who moved his capital to Zanzibar in the 19th century, actually led to a cultural renaissance of sorts.

Today, the stone towns face challenges of modernization and preservation. UNESCO World Heritage status has helped protect places like Lamu and Zanzibar's Stone Town, but balancing tourist demands with authentic cultural preservation remains difficult. The young generation, connected to global culture through the internet, sometimes views the old ways as backward, not realizing they carry a unique cultural legacy that took a thousand years to develop.

The music of Taarab perhaps best encapsulates the living spirit of Swahili culture. This musical genre blends Arabic maqam scales with African rhythms and Indian instrumentation, with lyrics in Kiswahili that often play with the language's multiple linguistic layers. Listening to a Taarab performance in an old stone town courtyard as the ocean breeze carries the scent of spices - this is where you truly feel the living pulse of a civilization born from the sea.

What makes the Swahili Coast's cultural synthesis remarkable is that it was never imposed by conquest or forced assimilation. Unlike many other blended cultures in history that emerged from empires or colonization, this one grew gradually through trade, marriage, and mutual interest. The stone towns weren't just trading posts but genuine crucibles where cultures met as relative equals and created something new together. This might explain why the Swahili cultural synthesis has proven so enduring - it was built on consent rather than coercion, on mutual benefit rather than domination.

As the Indian Ocean once again becomes a center of global economic activity, the ancient model of the Swahili Coast - where diverse cultures met and created something greater than the sum of their parts - might hold valuable lessons for our increasingly interconnected world. The stone towns stand not just as beautiful relics of the past, but as potential blueprints for a more harmonious future.

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By Benjamin Evans/May 20, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025