In the heart of Iran’s arid landscapes, where the sun scorches the earth and water is a precious rarity, lie the Persian Gardens—verdant oases that defy the harshness of their surroundings. These gardens are not merely spaces of beauty; they are profound embodiments of Persian philosophy, artistry, and a deep connection to nature. For centuries, they have served as sanctuaries of tranquility, symbols of paradise on earth, and reflections of a culture that finds harmony between the tangible and the spiritual.

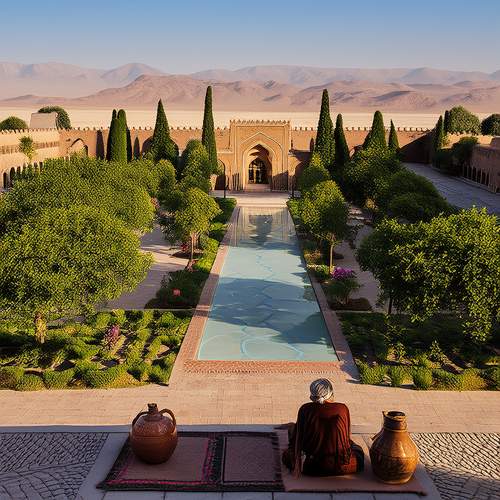

The Persian Garden, or “Bagh”, is a masterpiece of human ingenuity, designed to thrive in some of the most unforgiving environments. The ingenuity lies in its sophisticated irrigation systems, known as “qanats”, which channel underground water to nourish the gardens. This ancient technology, dating back thousands of years, transforms barren land into lush, thriving ecosystems. The gardens are meticulously laid out, often following a quadrilateral design divided by waterways, symbolizing the four Zoroastrian elements of sky, earth, water, and plants. This geometry is not accidental; it reflects a cosmic order, a microcosm of the universe as perceived by Persian thinkers.

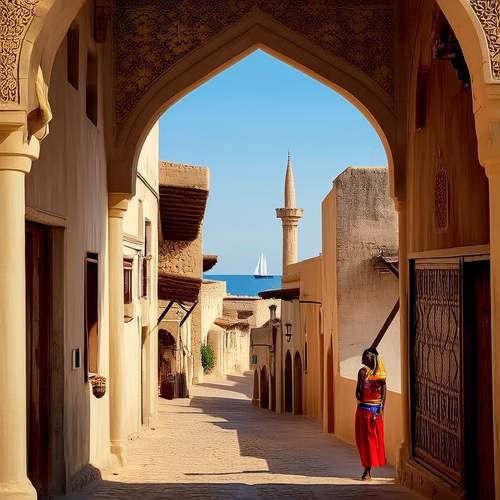

Walking through a Persian Garden is an experience that engages all the senses. The fragrance of roses and jasmine lingers in the air, the sound of flowing water soothes the mind, and the shade of towering cypress and fruit trees offers respite from the relentless sun. Every element is deliberate, from the symmetry of the pathways to the placement of pavilions and pools. These gardens were not just for leisure; they were spaces for contemplation, poetry, and philosophical discourse. Persian poets like Hafez and Saadi often drew inspiration from these serene settings, weaving the imagery of gardens into their verses as metaphors for spiritual enlightenment and the divine.

The concept of the Persian Garden transcends mere aesthetics; it is deeply rooted in the Persian worldview. In Islamic tradition, the garden is a representation of paradise, a promised reward for the righteous. The word “paradise” itself derives from the Old Persian “pairidaeza”, meaning a walled garden. This idea of an enclosed, perfect space resonates throughout Persian culture, symbolizing an ideal state of being where humans coexist harmoniously with nature. The garden becomes a bridge between the earthly and the celestial, a place where one can glimpse eternity.

One of the most renowned examples of Persian Gardens is the Eram Garden in Shiraz, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. With its towering cypress trees, fragrant orange groves, and reflective pools, Eram Garden is a living testament to Persian horticultural brilliance. Similarly, the Fin Garden in Kashan, with its intricate water features and historic bathhouse, tells stories of Persia’s royal past and its enduring love affair with nature. These gardens are not frozen in time; they continue to evolve, yet their essence remains unchanged—a testament to their timeless design.

The philosophy of the Persian Garden extends beyond its physical form. It embodies the Persian ethos of resilience and adaptation. In a land where water is scarce, the garden becomes a symbol of life’s persistence against adversity. It teaches the value of patience, planning, and respect for natural resources. Even today, as modern cities expand and environmental challenges grow, the Persian Garden offers lessons in sustainability and ecological balance. Its principles of water conservation and harmonious design are more relevant than ever in an era of climate crisis.

To visit a Persian Garden is to step into a world where nature and humanity are in perfect dialogue. It is a reminder that even in the harshest conditions, beauty and wisdom can flourish. These gardens are not just relics of the past; they are living philosophies, urging us to rethink our relationship with the environment and our place within the cosmos. In the silence of their shaded pathways and the murmur of their flowing streams, one can hear the echoes of ancient Persia—a civilization that saw the garden not just as a place, but as a state of mind.

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By Benjamin Evans/May 20, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025